Teaching Ideas

This is dedicated more to new teachers, ‘new’ meaning from the first day to anywhere within the first few years of teaching. In this issue I’d like to explain what a lesson plan is and later cover some basic points that could serve as guidelines when you have to come up with your own lesson plan. There will be a mix of ideas and suggestions, some helpful to a person just starting out and others that will take on more meaning once you have some experience. As with any guidelines, feel free to interpret them and their importance according to your needs, interests and situation.

Many soon-to-be teachers enroll in some kind of course before beginning work, or the place that will employ them provides some kind of orientation, briefly touching upon many of the important considerations including preparing a lesson plan. However, lesson planning, like classroom management or becoming familiar with the grammar, is something that takes a long time to develop. It’s you as a designer, placing activities onto a blank screen or piece of paper, determining their order, how long you expect them to last, and how they are carried out.

I remember myself with some 3 or 4 years into the field, often wondering what I was missing, what I could be doing differently to make a tighter class plan and how I could execute it in a cleaner, more effective way. Over the years and having taken many courses, attended many workshops, spoken with many people, read many articles and explored frequently within the classroom, I gradually came to a perspective of feeling much better about lesson planning. Then there came a time when I began working with newer teachers and trying to pass on some words of wisdom to help them along their paths. Most of it comes through experience, but some tips can be helpful, so I’ve compiled a short list that I hope might be useful to some of you.

Here is a brief listing of the themes that we’ll be looking at:

| A. What a lesson plan is | ||||

| 1. The form | ||||

| 2. Mapping out a rough lesson plan (some tips) | ||||

| 3. Keeping your lesson plan | ||||

| B. Some guidelines when writing up a lesson plan | ||||

| 1. Be aware of who your students are | 7. Clear end goals | |||

| 2. Clear Objectives | 8. Be flexible | |||

| 3. Student books | 9. Some logistics | |||

| 4. Closure | 10. Reflect | |||

| 5. Development | 11. Student involvement | |||

| 6. Backward Chaining | 12. Plan your next class shortly after this one | |||

| C. A few final words | ||||

| D. A few different lesson plans to look over | ||||

A. WHAT A LESSON PLAN IS

1. THE FORM

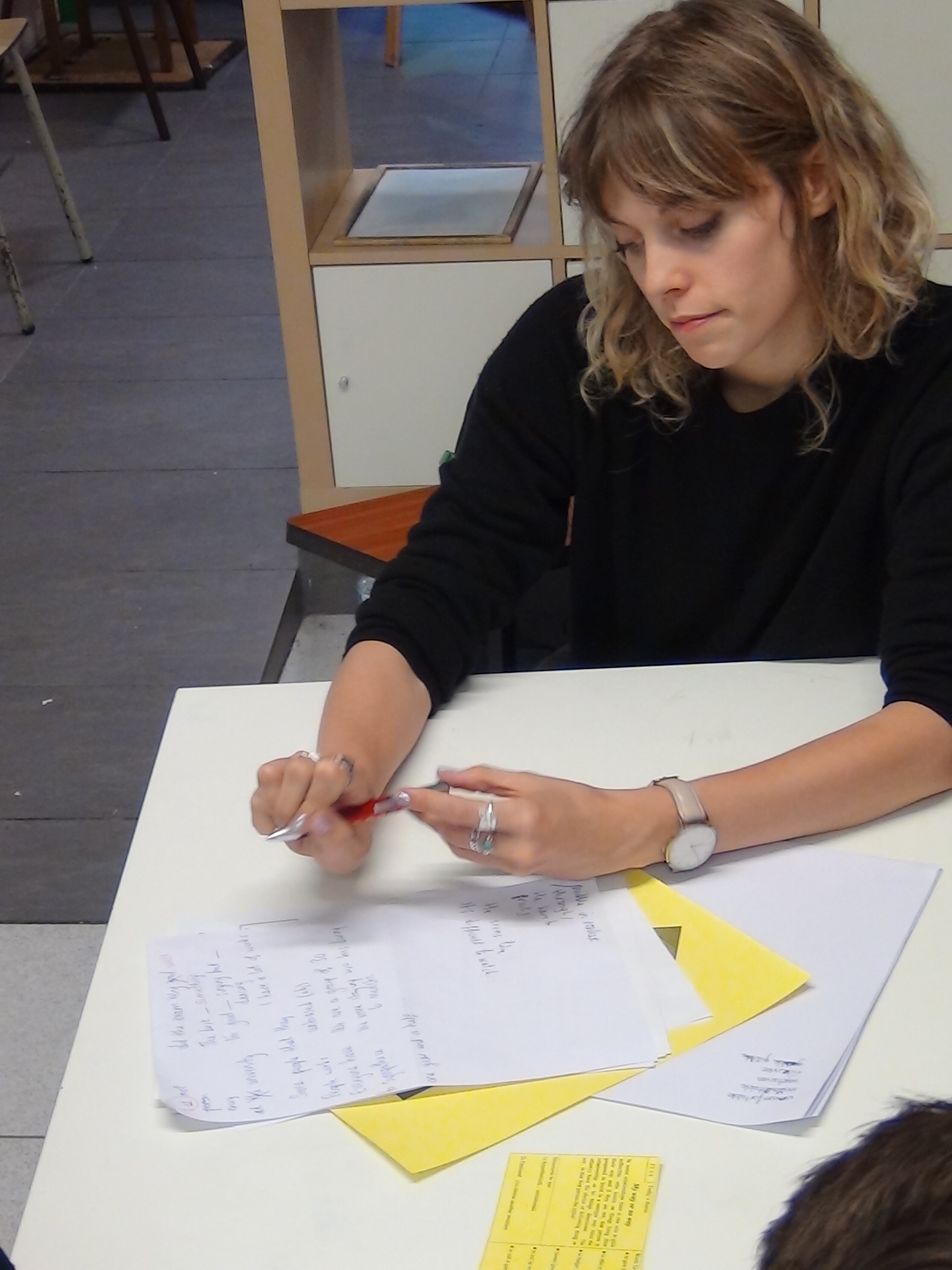

A lesson plan is a guide of what you want (or have) to do in your class. Chances are you will have a number of groups and each will have their own particular plan. Many standardized lesson plan forms have some information that is to be filled out at the top and the actual plan is spelled out in the bottom. In one school there could be a form for regular lesson plans, another for substitutions when a teacher is off sick and somebody has to fill in, and yet another lesson plan form for when the teacher will be observed by someone in administration, perhaps the director or a coordinator. Here is one such possible form:

If you scroll down this page you’ll find another copy of this lesson plan which you can print or download if you like. It has an additional note attached referring to the writing assigned for homework.

You can see at the top of the form that there are spaces laid out for the level, times & location of the class. Some forms have a space for which book and the page numbers you intend on covering. Maybe there will be a box for the general theme(s) of the class (such as cultural holidays or interesting new technology). Some forms have sections for grammar (verb tenses in the past), vocabulary (kitchen vocabulary) or phonology (‘ed’ pronunciation) covered. Perhaps there is another space for how many students are in the class and maybe even a class profile (8 students, 1 recently retired and 7 are going to university. Friendly but not very hard-working. Don’t often do homework but will participate well if the topic is interesting. Student X often comes late and has more difficulty speaking than the others, but knows the grammar quite well.)

You lay out your plan in the order you plan to execute it. The times you write are estimates as to how long you think the activity will last. (NOTE: If it is important that you do some key activities later in the class and you are taking longer than originally planned, you will have to quicken the pace or even eliminate some other activities so you will have time to do what is needed.) The interaction column refers to who is principally doing the action. For example:

S Ss (students) work individually S – S students work in pairs

Class the whole class is involved Ss (3) Ss work in groups of 3

Ss – T students speak to teacher T – Ss teacher talks to Ss

The above example of a lesson plan is one made up to demonstrate how one standardized form could appear. On this website there are different versions, depending on their function. Go to any lesson plan for APPETIZERS, MAIN COURSE or DESSERT and you can find a single page overview (Quickpage) or immediately after it is a more detailed version with step by step instructions. If you look in One-pagers, there is another format (click here to see an example) which resembles the one above in some ways, but remember that it is for a webpage and for personal use, not for any particular school.

2. MAPPING OUT A ROUGH LESSON PLAN

This can be a very daunting task the first few times you sit down, looking at the blank paper or form in front of you and wondering just how to go about it. Here are a few tips:

►Get an example to refer to. If possible, ask your school to provide you with a few examples (or at least a blank form if they have one) so you can have an idea of how they would like it approached. Also find out how many students (a class of two students will be approached differently than one of thirty). If that’s not a possibility, come up with your own, doing the best you can under the circumstances. You can always improve later on.

►Write down the general theme of what you want to cover. If your class is a long one, say 3 hours long, then you would write down several themes. This could be topic areas like ‘trends in popular music’ or ‘modern marriages’ or could be more directly related to the language like ‘prepositions of location’, ‘verb tenses’, ‘adjective formation’ or ‘pronunciation – syllable stress’.

►Decide on an objective or two. What is it that you want them to learn or be better able to do this class? For example, students will learn the 3 different ways to pronounce ‘ED’. Or ‘Students will learn different ways to describe objects according to size, shape and material’.

►Decide on what tasks or activities you want the students to do so they will make progress towards meeting those objectives. If you are using a course book of some kind, you can use those that are presented, or add your own changes. Remember as a standard rule of thumb you want to introduce the area of focus (ex: learn 6 new phrasal verbs), have them be aware of what they should know, and get them practicing.

►Consider the order of those activities. Maybe some are better earlier or later than originally planned.

►Consider the time needed to do each activity. Have an extra activity or two just in case they finish early.

►Consider different interactions. Make sure it isn’t only you speaking to them. Plan for them to interact in pairs, maybe again in different pairs, in small groups, as a class.

►Go through your rough plan again. Imagine the class materializing, each step of the way. Are the times you estimated appropriate? Are the students sufficiently prepared to go to the next step or eventually complete the task you are building them up to?

►Organize what is needed. Do you have enough photocopies for all the students? Will you be needing any other materials (board pens, maybe something to show the students, LEGO or something they will have to use)? If it is their first class it is very possible that not all the students will have their books, so maybe you will have to make copies of those pages you’ll be referring to in your first class.

►Anticipate difficulties. What happens if you have an odd number of students and not an even number which you prefer for a certain activity? Maybe you have more (or fewer) students than originally thought. What if the computer or the sound system doesn’t work? What if they don’t understand some of your instructions? Think of possible surprises or difficulties that might occur and how you might go about dealing with them.

►Go through your plan once again. Again imagine each step and how it might turn out. Make a few notes to yourself if you like. When you feel reasonably confident about it, try to feel good about it. Remember it will be your first or one of your first times and while it may not be perfect, it’s not expected to be. Have a bit of fun while you are in your role as a teacher and smile on occasion.

3. KEEPING YOUR LESSON PLANS

Some people keep a folder for every different kind of course they are teaching, or have taught. In that folder is every plan, worksheet, copies of pictures and links to websites for every class they have done in that course. If they ever have to teach that course again, they already have much of the work done. Of course if something didn’t work well in the previous course, you’d make a note of it and would try it in a different way next time around. If you do this, you will make your life much easier.

B. SOME GUIDELINES WHEN WRITING UP A LESSON PLAN

1. BE AWARE OF WHO YOUR STUDENTS ARE

I once had 3 different 90-minute classes back-to-back, and all the same level. I quickly learned that I couldn’t use the same lesson plan for all three classes. It just didn’t work. I had to adapt it to the personality of each group and the individuals that are part of it. Some activities were wonderful for one group but just didn’t go over for another. Some classes participate and explore a lot, ask many questions while others don’t easily volunteer more than the minimum, or even that. Perhaps they are exceptionally timid, or tired after a long day’s work, or the cultural or interpersonal dynamics play an inhibiting role in their expression. There are many factors that come into play and if you can work with them, then your lesson plan can take shape in a way that will be rewarding for all concerned.

Some groups need more examples and more practice activities, to be led, supported more. Others are eager to work on their own with a minimum of direction. All this affects your lesson plan. So try things out and see how the students respond. Not everything will be met with astounding success, but as you get to know your students better, you can personalize your lesson plans to better assist them to becoming more effective language users.

2. CLEAR OBJECTIVES

This, actually, is to me and most experienced teachers I know, the foremost thrust of any lesson plan. I put it in second place because how it takes shape always depends on the students you have, their needs and abilities, what motivates them or captures their interest. But remember, the contents (a particular reading or listening text, a game, some vocabulary or grammar work, a theme for discussion) are there to help the students come closer to the goals of increasing their understanding and use of the language. You decide which activities and how to approach them with that in mind. Usually this means you have to be clear in what your objectives are, and wherever possible, be able to determine if your students are making progress or not.

For example: Objective: Students do a reading. or Students speak about last weekend.

This is not usually considered an objective. It’s simply a general description of what the activity is. But this is what many teachers write in their lesson plans when stating what the objective is. Sometimes there are variations but they are not any clearer.

Example: Students practice their speaking. or Students practice their reading skills. (Which ones?)

Maybe the student reads the text but understands absolutely nothing. In theory, the student did a reading and therefore successfully accomplished your objective of doing a reading task.

A better objective would be – to determine to what extent the students can understand a challenging authentic text at an intermediate level (and create a number of comprehension questions to check this), and/or a different objective – to demonstrate different ways how important information from a difficult text can be extracted (and you elicit/provide those different ways with examples which can be later applied to a new text).

Being able to create clear objectives and mold them into something effective (and I would say even powerful in their execution), is something that takes a long time and much frustration for the teacher along the way. But the effort is well worth it. You not only feel much more capable and confident about your teaching, but the students increase their respect for you and feel their own motivation on the rise.

While this is a complex area and a long journey in becoming familiar with it, here are a few starting out tips:

- a) Objective ≠ task Remember the objective is NOT the task. The task is there to help the students better meet the objective. The tasks are the means and the objectives are the ends.

- b) Why? If a student ever asks you why they are doing any particular activity, you should be able to easily respond by pointing out just what it is they are working on or towards, and how this task in question has been deliberately placed in your lesson plan to help them with just that. (ex: Maybe the student didn’t like the theme of the reading, but the task will help him/her by serving as a reference to what is expected of them in the writing homework assignment they will soon be receiving.)

- c) Quantify It is almost always possible to ‘quantify’ your objectives in your lesson plan if you deliberately structure them that way. Think of

1- how you can know if any given student did a task successfully (Test or quiz them, look for ways of verification)

2-how well that student did (How can you grade the students’ achievement in meeting the objective and differences between students?)

3-how the task has brought them closer to meeting that objective, or not (This is the most difficult. If the objective is a long-term goal, for example, it is not easy to measure concrete progress towards it. But you still want to continue in that direction, making future decisions in planning that will strengthen the students’ progress.)

3. STUDENT BOOKS

The student book, the workbook, the teacher’s book are tools, nothing more.

Many teachers feel obliged to follow the style and the content of what they are given. (And in many schools, it might be obligatory. We’re going to assume here that the teacher has at least some flexibility to maneuver in both lesson planning and its execution.)

Course materials are getting better all the time and following the suggestions that accompany them often lead to good classes. However, most courses are not designed for the teacher to follow every single exercise in the book, nor is there time to do so. It’s possible you may even have more than one group of students at the same level, but they are quite different in attitude or ability and not all the activities work out equally well, so it’s important to anticipate this in your lesson plan and adapt it to your various situations.

Some suggestions regarding the use of student books in your lesson plans:

Think clearly of what your objectives are (what you want the students, or you, to accomplish) and how the book or extra resources can help you achieve those goals. This may mean eliminating, substituting, supplementing or modifying that provided material.

- Look at what the student and teacher’s books have to offer. You don’t have to re-invent the wheel. Quite often those activities can be good ones. But have an idea why you want to include those that appeal to you. Will they contribute to your class becoming a good one, and in what way?

- Eliminate – you don’t have time to do all the exercises. Does activity X in the book REALLY help your students meet your goals? If there are activities that don’t appeal to you or don’t help you in meeting your objectives, don’t do them.

- Substitute or Supplement – If it doesn’t (entirely) meet your objectives, look for materials or an activity in another course book or on the internet. Some teachers even come up with their own material which directly helps them guide the students towards meeting those objectives.

- Modify – You could cut out some parts of the exercise which are not helpful or do them in a different way. Here are a few examples of how you could do that:

►Change the listening to a reading exercise with a gap-fill (or other kind of task). Later the students can check their answers with the audioscript. (It’s not necessary but you could still follow it all up with the listening after everything is done.)

►Choose which vocabulary you prefer the students focus in on, not what the student book suggests (and understand why you are selecting your version). One mistake many teachers starting out make is to make a long list of vocabulary to cover. This still could be done, but it’s tricky to do well. Generally speaking, it’s more effective to concentrate on a short list of items that really are new to the students, and to do several different activities with those items, rather than to keep giving them even more to get through. This is referring to within a single lesson plan, of course.

►Select a section. Maybe the listening or the reading is too long. Then just do the first or a different part if that sufficiently meets your needs. The same can be done if a grammar exercise is too long. If it is too short, add more. If it’s too difficult or too easy, make the changes.

►Have students read parts of the provided text aloud to acquaint them with some aspect(s) of phonology (such as connected speech or ‘ed’ pronunciation).

►You like the general idea of how the exercise is presented in the student book, but not some specifics, so make your own questions in the same style, or in a different way.

►Change the order. Perhaps you want to deal with the vocabulary before the reading or listening rather than after it as introduced in the book. (Again try to think why you are doing this – how this way would help the students more in achieving the aims you are setting. To meet those goals, you might have to alter the exercise as well. For example, it’s one kind of exercise to ask the students to determine the meaning of vocabulary from the context of a text they have recently read, but it’s another kind altogether to have them work with vocabulary without that context. Do you elicit / provide definitions or synonyms, matching exercises, have example sentences or gap-fills? Why would you prefer to do this before the text and not after it? – one answer is that you could use the coming text to reinforce that vocabulary you’ve gone over as it provides a context.)

►Repetition. You could photocopy an exercise done in a previous class or earlier in the same class and get them to reapply what they have learned (in theory).

►Personalize it. Make modifications so they are better adapted to the class, the individual students, or even yourself. This could be with references to people, places of work, recreation and interests, holidays, routines, dreams or approaches.

►Have the students change it, perhaps by you supplying some suggestions or options. For example, different students change different sections of a text and later the other students have to detect what those changes are. Or you go over a letter in class but now you want them to rewrite it with an angry or apologetic tone, or with different events or outcomes.

It’s often easier to change something that already exists than to create something new from scratch. If you come across an exercise in a student book or other resource that you doesn’t quite meet your needs, find a way to alter it accordingly.

4. CLOSURE

Think of where you want the students to go in this class. Will they leave the class with a clear idea of having made progress in some way? They may not be experts yet, but it is possible to note that they have increased their understanding or use of the language to some degree. Do they know that? If you think that it may not be easily obvious, try to work in an activity along those lines, such as the students quizzing themselves on the new vocabulary they have just covered or they use it in their speaking. Let them know in some way that they have completed something, even if it is but a step in the right direction.

Closure can refer to tying an activity up before moving on to something new. It can also refer to correcting that exercise you set for homework last class. Or getting back to them as you promised about a difficult question they had asked you. Make room for closure in your lesson plans. It will make your classes much stronger and well respected.

5. DEVELOPMENT

If you do a quick exercise like going over a short list of new vocabulary items, know that that won’t be enough. As mentioned previously, take it further with another activity, applying what they have learned. It could be recognition in a listening or reading text, doing exercises like matching, definition-making or gap-fills, using it in writing or speaking. Maybe deal with it in layers, such as first cover the pronunciation, then the meaning, then see how it’s used (reading or listening), explore areas that splinter off momentarily but are directly relevant such as word-formation (changing the verb to adjective or noun forms) or synonyms (other ways of expressing something similar, but also noting how they are not exactly the same), and of course using it in production (speaking or writing).

Development can also refer to the grander scheme of things, not just within one particular lesson plan, but also to all of them within a course and the students’ general progress in language learning. This means that in future lesson plans there will be further developmental work done as well as referring to what has been done in previous ones.

6. BACKWARD CHAINING

One frequent approach to lesson planning is to plan for a task that you’d like your students to do at the end of (or some point in) the class.

Example of a task for a low level class:

maintain a conversation for 5 minutes, volunteering & expanding on personal information and asking & responding to what another person says

Example of a task for a higher level class:

incorporate into the dialogue at least 2 of the structures using inversion for emphasis (not only, not once, etc) as well as supplying further details or reasons.

So how would the students get to that point? You would have to introduce the various elements in some way, have the students explore them further to be better acquainted with them, put them into practice, and eventually see if they can do it on their own. The idea is to break it up into a series of steps that prepare them for what is needed. It could well be the case that one step that might be troublesome or difficult for the students might have to be broken down into further substeps. Very often teachers ask the students to make a big jump to carry out a task they are not quite yet ready for.

When planning the sequence of elements they want to cover teachers often start at the beginning and try to think through what is needed to get to the desired stage or task. This is certainly one way to approach it but backward chaining refers to thinking of that end task and working backwards. What would be the step before getting to that point? What would the students need to know or have practiced? What about to get to that second last step? What preparation might be necessary for that? And that is how the idea of backward chaining could be adapted to lesson planning. It is one technique that can save you some time in lesson planning, and also help you conceptualize some necessary steps and contribute to a tighter lesson plan.

7. CLEAR END GOALS

Imagine you want your low level class to speak without your intervention about last weekend. The speaking will be for an extended time (5 minutes). That is the final task you want to end your class with. They have already gone over some verb tenses in the past (past simple and past continuous, for example), verb forms (irregular and regular verbs), ed pronunciation of regular verbs, some possible activities to refer to (go out, order a pizza, go dancing, stay home, etc), how to ask and respond to questions, how to make comments and volunteer more information, and whatever you feel they may need for that coming conversation. You’ve been working on all these elements and now is the time to put it together and have them speak more freely. Yet it is not uncommon for a number of students to feel a little lacking in direction and finish all they feel they can do in their conversation task in 45 seconds, not the desired 5 minutes of extended speaking.

If one of the objectives is to have the students become a little more independent, then that objective is not fully achieved if the teacher is frequently aiding or having to aid the students. This final task could be broken down into several substeps. Here is an example of 5 separate but successive tasks, the first four leading up to the final one, rather than jumping directly to it.

- 1 The class asks the teacher (you) what you did last night.

You respond, provide some details (modelling what you expect from them later) and the class asks further questions based on what you said (and you prompt them to do this).

Remember to step in and out of your different roles: one, a person responding to their questions and comments and two, the teacher guiding them on how to better use the language. You could direct them to use certain structures (What did you do after that? Why did you…?), correct their pronunciation, point out good participation and anything else you feel will encourage them along the right paths.

- 2 Only one or two students (you decide who) ask you about what you did last weekend.

You respond as you did previously, helping when necessary, but trying to get them to do most of it on their own. Also introduce the idea that you can ask the interrogators and make comments yourself (“That’s interesting.” “I did something like that too!”) . You want it more interactive than one-way questioning.

- 3 Now the focus is on another student to respond to questions about last weekend. (You are out of the picture except to give minor guidance so they can carry out the task successfully.) Appoint one or two other students to begin the questioning, but also encourage the first student to ask them questions and make comments too.

- 4 Place students into pairs. They now have to ask and respond to each other about questions of last weekend. This is the same as the last task except now everybody in the class participates. If the students find it difficult you could have Student As ask Student Bs only, then after a few minutes, change roles.

You are still there, monitoring, prompting, helping, correcting and guiding, but keep it to a minimum if possible. Most new teachers stop here. But the students are still quite dependent on you. This leads us to the last stage:

- 5 Students are placed into new pairs. They are to ask / speak about last weekend.

You tell them before they begin that they are on their own. They have to get through it, mistakes and all, without your help. Later, when the activity is done, you will respond to any doubts they might have.

I have observed literally hundreds of teachers and what very frequently happens is that the ‘freer speaking’ activity planned at the end of the class is not so free. It usually turns out that the teacher is there helping and guiding them, even fine-tuning instructions or expectations that weren’t clearly understood by the students beforehand. This brings me to point out two things. Firstly, the teacher might not have a clear idea of what a freer speaking might be (they mistakenly think substep #4 is the final task when in fact you are striving towards #5) and secondly, the teacher hasn’t prepared the students enough for the task. In this example there are 5 separate speaking tasks, the first four of which, plus all the previous preparatory work are leading to the final one.

Three last points.

The title of this section is ‘Clear End Goals’ which refers to looking at the end task and asking yourself if you and your students achieved what you set out to do. Deciding whether or not you and the students were successful often depends upon how the task was carried out. You want to set up the task in such a way that you can easily see if the task was completed and how well it was done. Evaluation should include looking at all the steps along the way as well. Perhaps the inclusion of some step contributed much to the successful execution of the activity. The steps are determined by what the student needs to know and practice beforehand. If you can’t anticipate them and your class doesn’t turn out the way you had hoped it would, think about what happened and in hindsight, think of what steps you could have inserted or done differently that would have helped the end result.

It is often a good idea to ‘close’ the final speaking activity by making a few general comments on how well the students did it and perhaps by addressing a few mistakes or giving a few tips for future such activities. Remember you don’t want to interfere with their speaking in the final task, but if they have doubts, then after it is done, the students can raise any questions or comments they wish to communicate.

New teachers often find they don’t have time in the class to get to the final task they had been building up to. In an official observation, this is something you definitely want to include. In a normal class without the presence of an observer, you have to make different judgement calls. If the class needs more time to practice earlier stages, then it is perfectly acceptable to give them the opportunity and the guidance they need. You can plan your next class to go through some preliminary stages, repeating some things covered in the current class and adding whatever you feel necessary to bring them to that final task. Again, think of what you want them to produce, and what information / practice / guidance they need to get to that point.

8. BE FLEXIBLE

You have your lesson plan. You’ve estimated how long each part might take and partway into the class you’re discovering that it isn’t going as planned. That’s alright. It’s a very typical situation but quite unnerving for new teachers. Maybe the students might need more time or activities to practice or even just to better grasp what is expected of them. Or maybe they catch on quicker than you anticipated. Be prepared to have backup when needed. Backup could be extra activities if you finish all your lesson plan too quickly and there is 25 minutes remaining in your class. Backup can also mean extra activities if your students need further practice, something to help them become more familiar with something which requires time and experience.

It’s also possible you planned these wonderful activities for them and normally this is your favourite group and almost everything goes over well. But today nothing is working out. Maybe many of them had a bad day at work, it’s cold and miserable outside, their favourite football team just lost,… . You might have to change your approach and your plans for the class mid-stream.

There is another perspective that can unite with flexibility. We often stick to the tried and true, a limited group of approaches and materials that have worked reasonably well in the past. There’s nothing wrong with that, but it is also a good idea to stretch your limits every so often. The world we are living in is now constantly changing and providing people with ever more information. Investigate and tap into what is being offered, finding alternative ways of doing things, including doing some peer observations where you can see somebody else in action. Having a wider repertoire and range of approaches will help you in a few tight spots. Much learning (be it the teacher’s or the student’s) comes from experience so give yourself permission to experiment or deviate from the prescribed path on occasion. There are surprises waiting for you to discover them.

9. LOGISTICS

The class plan you have on paper might seem pretty solid, but there are many factors that come into play which can affect its success. Of course being flexible and able to improvise will help you out in a tight situation, but running through in your mind how things not only are going to work but how they might work will help prepare you for various surprises. For example you plan on teaching pronouns to a low level group. The lesson plan includes clear instructions and referencing, good written and speaking activities, and more. When you enter the class there are only two students, both male. Or both female. Or you have a class made up mostly of one gender. So this makes it difficult to refer to ‘us’ or ‘them’ for a class of two, or ‘she’ or ‘he’ in a way that utilizes the people in the classroom. So bring a few photos or name tags that you can tape onto nearby chairs.

Running through the logistics (how things will work / flow) of your planned class, there are many factors to consider. For example:

● how you approach instructions Do they need modelled examples or guided explanations, or can they go straight into what you want them to do?

● how you decide on the interactions Not why – that consideration would fall more into the category of objectives – but how and when and in what way. If you want them to move around or change partners or work in groups of 4, do the seating arrangements and furniture allow for these interactions? What can be done to facilitate them?

● how the room temperature, lighting, acoustics, size and layout affect what you want done Maybe the seating arrangement is very confining but there is a more spacious area in one part of the room which you can use. Get the students out of their seats, standing up and moving around in that space. If too many students, have one group use it while the rest work on a different activity, then change.

● how big or well your blackboard / whiteboard / screen works If you can’t erase the words well to write something new, if it’s too small, then you might want to consider photocopies or links to webpages. If it’s big, you can leave some references up for later use while you are working on something different.

● the personality and abilities of your students affect what you plan and its flow as mentioned in the first area of consideration Will this group willingly participate like the other one did? If they won’t, then you might have to change how you approach this element in your lesson plan.

● availability of technology This includes how well it works. What do you do when something doesn’t work as you had planned. This happens a lot. You can and often have to depend on it, but be prepared for Plan B if one day it doesn’t. The students are still there, waiting for something, and you are expected to go on with the show.

● props Some teachers use them and others don’t. It could be a water pistol and a Bogart style hat to help a role-play, it could be moving a table to represent a wall, anything you can find in or bring to the class that will add focus and be useful in some way.

● timing This is very important although some teachers are able to write their lesson plans with just a general feel of the timing and it usually works out fine. When starting out, though, pay special attention to how long you will need for the execution of each part of your plan. You might find that you will have to make adjustments.

Logistics is important. The practical look at how things are going to work, at least optimally. With built in Plan Bs. The better you can anticipate and deal with factors, the better you can use the existing situations to your advantage.

10. REFLECT

Some new (and even very experienced) teachers keep a journal, writing down what happened in their classes that day. If something went well, any ideas why it was so successful? What were you doing well? What else may have contributed? Could you do it again with another group? Maybe it wasn’t successful. How could you have done it differently? What particular factors played a part?

After many years of experience I don’t keep a journal like in my starting years (which I found very helpful in my growth as a teacher), but I do have various places that I transfer my ideas and perspectives. When I am in class I still have a copy of my lesson plan in front of me and I frequently scribble notes onto it as insights occur, finding ways to improve something, or reminders that I should keep note of.

It’s not always easy to pinpoint any one particular influencing factor but with practice, you get a feel for it and more clarity enters your perception of what is happening in your classes. That practice includes a long history of reflection, wondering about the dynamics of what comes into play. When ideas form after such reflection, bounce them off other teachers or try to apply them in class to see what effect they may have.

11. STUDENT INVOLVEMENT

The lesson plan shouldn’t be mostly you lecturing your students. You want to get them involved, capturing their interest in the beginning (set the scene with a game, a thought-provoking comment or question, or somehow demonstrating their need to work on that area you are introducing), and keep them engaged right until the end of the class. It doesn’t always have to be dynamic and fun and entertaining. In fact it would be better for all concerned if they could appreciate the benefits of learning and making progress for their own sake.

There are many ways to keep their interest. They need structure and to be assured that you are leading them in a productive way that will gain results. Having well-developed activities with clear objectives and a good closure contributes much towards that end. Showing your students respect in how you interact with them individually and as a group goes a long way. Incorporate issues that are important to them (maybe do a needs analysis, a feedback session and certainly you can gather relevant information from little chats with them or being perceptive of how they approach things in class).

Make sure they participate frequently and in a variety of ways. By observing them in pairwork and groupwork you can get a better idea of what works with them, what motivates them, what they find difficult. All of this can serve as an ongoing source of ideas which can stimulate activities, tasks and objectives to be placed in your next lesson plans. And by granting them the opportunity to work at their pace, express themselves in ways that they would like to, they feel a greater belonging to the group and the atmosphere you are helping to create. They want to become involved more. The effort and preparation you put into these aspects will pay back in rewards in multifold. It will make your job and your planning much easier and more satisfying in the long run.

12. PLAN YOUR NEXT CLASS SHORTLY AFTER THIS ONE

It’s a simple concept but put into practice, it can save you tons of time and head-scratching. During your class when something occurs to you, jot it down somewhere, even right on your current lesson plan. Maybe it’s obvious that the students need more practice with something or you have an idea that would work very well next class or it’s time to finally get around to doing a listening. Write it down before you forget. If you have a few minutes when the class is clearing out, look at the book in front of you, see where you left off and what’s coming up, and while everything is fresh in your mind, scratch out a rough plan of where to go from here. Later, when you have more time, fill in the details.

This makes it much easier than doing it 5 days later, the night before you have the class again. You are trying to remember what you did because your notes aren’t 100% clear, and you’re not sure what to do now. This is much more time-consuming and can add to an already heavy workload. Try it both ways, right after your class and a few days later. You’ll see the difference.

C A FEW FINAL WORDS

These, then, are but a few considerations. Many teachers have found them to be helpful while taking on the task of coming up with a lesson plan that they can feel good about.

One last word of advice. For some, one of the reasons teaching is a fascinating vocation is because the areas and factors where one could learn more about are almost endless. It is normal, especially for teachers just starting out, to experience a desire to spend a very long time planning their classes. Remember it could well take years before you feel comfortable with those plans. It’s as simple as that. One cannot conquer Rome in a day, so try spreading it out. Maybe choose a couple of projects to work on (ex: clear instructions, boardwork, pronunciation, some aspect of grammar) and a few weeks or months later focus on something else (ex: clearer objectives, inclusion of closure, another aspect of grammar or classroom management). Perhaps place a time limit on how much time you are going to dedicate to lesson planning. Give yourself time to learn, to develop, and also to enjoy other things that life has to offer outside of the world of teaching. Start a new hobby, go out with your friends, enjoy a good book or TV show. It’s always best to place teaching into a bigger picture perspective. You’ll get better, and so will your lesson planning.

D. A FEW DIFFERENT LESSON PLANS TO LOOK OVER

SOME EXAMPLES OF LESSON PLANS ON THIS WEBSITE

NOTE: The following examples are for the webpage, to help walk different teachers through the lesson plan.

When writing a plan for yourself, you won’t need nearly as much detail. See the example above for a possible model to use in your own lesson plans.

Appetizer 1-1: THE ALPHABET

See the Quickpage for a fast one-page summary and the Class Plan for a more detailed version.

Main Course 2-1: SMOOTH N STICKY

See the Quickpage for a fast one-page summary and the Class Plan for a more detailed version.

Dessert 1-3: CANCER CAREFREE

See the Quickpage for a fast one-page summary and the Class Plan for a more detailed version.

Each of these three examples actually has two lesson plans. There is the ‘Quickpage‘ which is a one-page summary and handy for teachers already familiar &/or experienced with what to do. And there is the longer more detailed lesson plan. This second class plan is designed for those teachers who want to know more how the activities on this website could be approached, but it is not recommended to use as a model for one’s own lesson plans. It is simply too time-consuming. It is also unnecessary. I wrote the long versions with the assumption that the teacher reading it might not be familiar with how I approach teaching or with other lesson plans on this site. If you are writing for yourself, you can use symbols and abbreviations, and you won’t have to spell everything out (although for doing something complicated or unfamiliar, sometimes those extra notes could be helpful). If you like how the Quickpage is designed, or even want to use it as a guide for one of your own classes, you can download or print it as a reference.

Sometimes you’ll find that circumstances might lead you to approach lesson planning in a different way. This means that the format you use and the approach you take might be somewhat different to the one you’re accustomed to. Don’t be afraid to try new ways, especially if you’re a bit stuck and not sure where to go. The following 4 examples are similar yet different approaches which strive to better reflect the objectives of the activities they are representing.

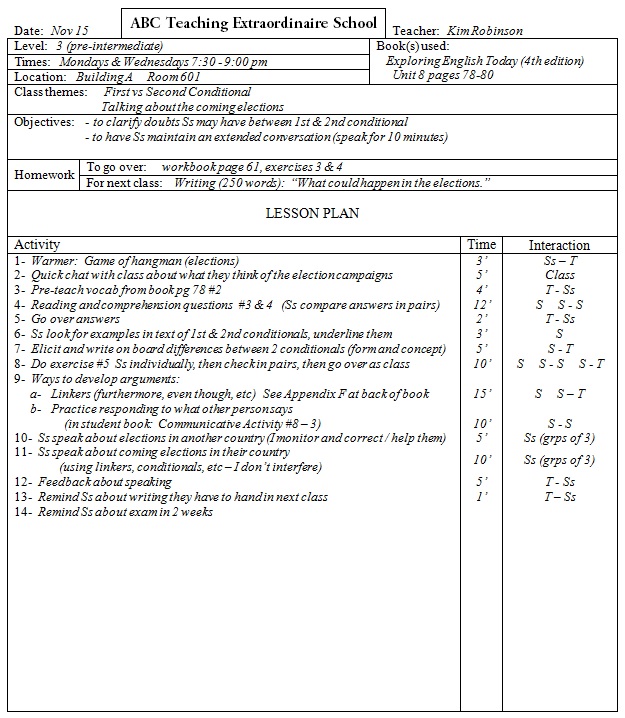

Today’s Theme TT 4-1

Nothing like a home-cooked meal

To encourage use of new vocabulary

(with an option of grammar) in the students’ speaking

A simple lesson plan outlined in Suggested General Approach

Some suggestions for pre- and post- task speaking and examples of how the optional grammar could be applied

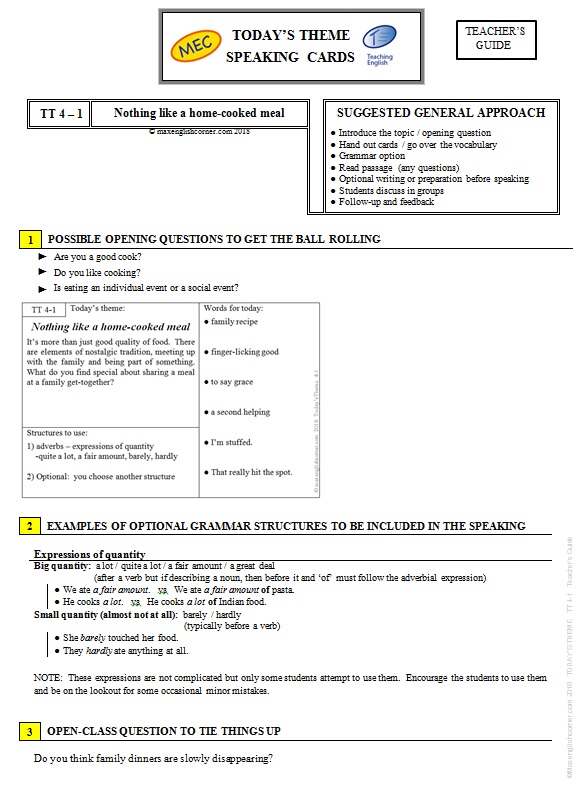

HST Narratives HST 1 – HST 7

Suggested General Approach

To expose students to authentic reading texts

and have them speak about some of the themes that arise

Lesson plans here are dedicated to offering a variety of options in exploring not only the story but also ways for the students to learn about & use the language. See example for Two Dates. The complete lesson plan for each part is offered in the orange boxes.

HST Narratives S’MORE STORIES

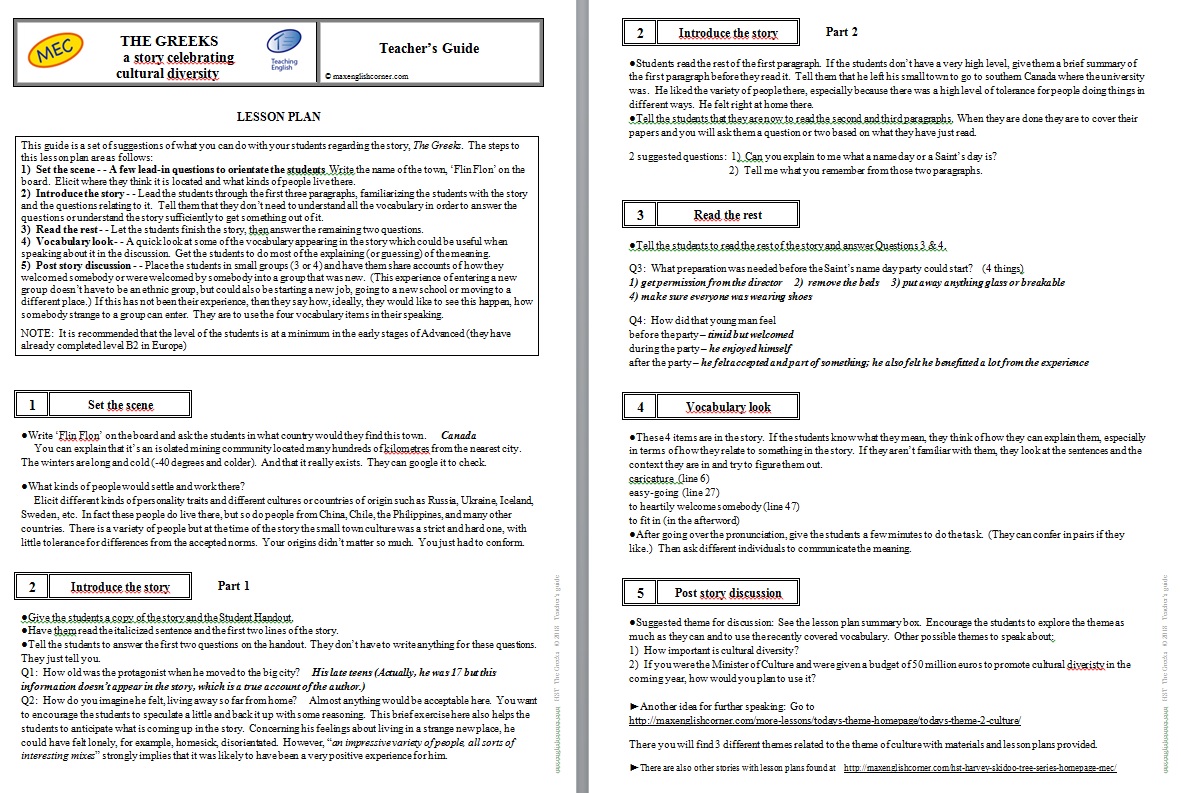

The Greeks

To expose students to authentic reading texts

and have them speak about some of the themes that arise

This is a simplified version. (The lesson plans for the first 7 stories offer more options to explore.) Reading skills, vocabulary and speaking is still encouraged but grammar is not directly part of the lesson plan. To see the story and student handout click here.