Using the PPP Model

If you aren’t familiar with the PPP model of lesson planning, then it is a very good idea to go to The PPP Model Explained and get some understanding of how it works. This page is dedicated to applying those principles to create a lesson plan in that style.

The section below is more about how to go about lesson planning in general as well as a suggestion on the order you may want to approach it. This is followed by some more tips and later two sets of guidelines, a longer version and a shorter one. They are reference sheets that give you some reminders of what that stage in the lesson plan consists of as well as a list of possible activities you could do in that stage. You can print or download either of these guides and you may find them useful when preparing your own lesson plans.

Imagine you have a reasonable understanding of what the PPP model is and you want to put together a plan following that model. Many if not most teachers in their first months of teaching take a very long time to write each one, PPP model or not. It doesn’t matter where you fit into the continuum of lesson planning time, but reflect a bit if you are on either extreme. If you can get one off in 20 minutes, it is likely you are either very experienced, most of the work has already been done for you or you haven’t really thought it through very much.

If it is taking you many hours, part of that investment of time could be beneficial because you are still learning how to approach a variety of elements. Part of that learning curve includes struggling to figure out where to go next or deciding how to go about making some major changes, and you start again. It’s up to you to decide how valuable that investment is to you, but be careful that you aren’t being excessively meticulous or perfectionist. As you will discover, there are many ways to approach teaching, plus it is a dynamic interaction. That means it is very possible that some of what you plan to happen may not occur or if it does, not in the way you expected. Try to get a reasonably practical lesson plan together and if you are enthusiastic in exploring lesson planning more profoundly, limit it to one or two themes of pursuit only. (For example, maybe you want to deliberately structure your lesson plan in a way that you elicit more information from the students than you lecture to them, or you want to try out different ways of approaching your boardwork.) Don’t try to take on mastering many areas of teaching in each lesson plan because you’ll just burn yourself out by trying to do everything perfectly.

So, in other words, expect to take time to get familiar with lesson planning, and remember that you can’t master everything in one or a few sessions. Be patient and selective about what elements you want to improve on in your lesson plan. Get a reasonably solid lesson plan together and learn to be happy with focusing on one or two themes to explore a little deeper. You will see better progress, have more directed perspectives and insights, feel more motivated, and you will have more time to do other things in your life. And you won’t burn out.

A GETTING STARTED

Here is one way you can approach your lesson planning:

Look at templates or examples your school uses to have a general idea of how to go about it. If you are in a school or course which provides those templates and has you fill them out, then do so. These templates are designed to have the teachers follow and include the contents and order of that model by filling in the cells presented in a table format. Some teachers find that very difficult to follow when trying to come up with their own lesson plan. In your struggles with trying to figure out how to do it, you might come across a different way that works for you better. That’s fine as long as you also (perhaps after completing it your way) hand in that form in the required way. (And if there is no required form, then create your own template that best suits you.) Here is a suggested alternative (that works for me) you can consider, but remember that if there is an official form you have to complete, then you transfer the info to it later and add any other necessary information. This, then, is a way to approach the initial rough planning and you can fine tune or adapt it later if need be.

1) Think of what you want to do. And jot it down.

●What do you want your students to work on next class?

●Define your objectives as clearly as possible.

●Decide on the theme for your class.

A certain area of grammar? Fluency in their speaking? Improve their listening skills? Pronunciation?

Don’t say, “Do some speaking.” Think of subskills. For example, ‘adding examples and explanations to justify opinions.’

Don’t say, “Past simple.” What do they have to work on? Is it ED pronunciation, irregular verbs, making questions, maintaining a short conversation using the past simple (speak about last weekend with your partner and see how it was different or the same)?

What is the theme that will run through many (perhaps all) of the activities you are going to plan? For example, your worst holiday, new technology, romantic relationships, pets, finding a job, health issues, etc. Whatever theme you choose will be used in the initial Context speaking activity, in the reading or listening, in your Presentation, in your Practice exercises and definitely in your Production activity.

2) Think of how you are going to do it (in general). Outline your class.

●Warmer (Context)

●Input

Input 1 – Reading/Listening for gist

Input 2 – Reading/Listening for specific information

●Presentation

●Practice (several activities)

●Production

This is the general suggested order, although there is some flexibility. For example, maybe the students are struggling with a Practice activity and you feel you have to do a new Presentation to clear up a few points. Then you continue with more Practice activities. If this happens in the class spontaneously, then you improvise to accommodate those developments. If you can anticipate those events before the class, you can try to deal with them in your lesson plan.

These are the five general stages/activities, but obviously you will have a few activities for the Practice stage and you may want to break up the Presentation stage into a few parts.

First plot out what you generally want to do in each of the sections, and not necessarily in this order. Later you can add further details.

Complete the above outline with a few initial details and approach each section in the order that seems easiest for you.

- For example, maybe you can fill in the Presentation first because that will reflect your objectives. Just write down what it is that you want your students to focus on / learn in this class, and a little about how you may go about doing that (ex: a particular verb tense – look at its form, how it works in a sentence and in a question, what situations to use it in, some examples to look at, maybe some special features or considerations to bring the students’ attention to. Are you going to use the board, a handout, some other references? How might you engage the students to actively focus on this information?)

- Then you can do the Production next, identifying how you want the students to demonstrate that they have learned what you wanted to teach them. (Some speaking activity like a conversation, role-play or debate that reflects the theme and is a good opportunity to use the target language.)

- Then the Practice activities. What can the students do after the Presentation to better prepare them for the coming Production stage? Think of several activities which help them first become more familiar with important elements of the target language. Don’t forget to include one or more Practice activities that include speaking if your Production activity is a speaking one. As a rule of thumb, have the first activity or two focused on the form of the target language and maybe when to use it. The later Practice activities should include speaking and in a freer style.

- After that you may want to work on your Input stage where you find a listening or reading or video that reflects the theme and ideally has some of the language you want to look at. (For example, imagine your theme is a bad vacation so you check some YouTube videos of people talking about a terrible vacation they have had. You also want the students to practice the past continuous, so you check to see if that target language is included. If not, then you would search for another video. Maybe you find one, but much of the language is too complex for the low level you are teaching. So you continue your search. You find one, but it is too long. However, you don’t have to show it all and you decide on an excerpt that is for three minutes. From that you work out your Gist and Specific Detail questions (Input tasks 1 & 2).

- Now that you have the general lesson plan worked out, you have a better idea of how to start off the class with a Warmer (Context). Think of something that gets the students thinking about the theme such as describing pictures of unhappy tourists or you write a light discussion topic on the board to be explored in groups of three (ex: What are some things that could go wrong on your holiday?). Be a little careful with this Context activity. Here are three things to consider:

1- Keep it light and engaging. Nothing too heavy and dense. Remember that the target language isn’t really looked at until much later in the Presentation stage.

2- Keep it to the theme of the class, that ‘thread’ that will be running through most of your activities. In this activity, your main goal is to introduce that theme and get your students thinking and talking about it.

3- Many times when teachers first come up with a speaking theme (ex: Describe your worst holiday) for the warmer, it just might be better placed in the Production stage activity. After the students learn some relevant vocabulary or a particular grammatical structure, they might be in a better position to apply that new knowledge in the Production after recently been exposed to it in the Presentation stage and practiced it (in the Practice stage). So think what kind of activity would be better suited as a warmer, and which would be used in the Production activity.

NOTE: You may follow this or develop your own way and order of doing things. And there will be times that you will do things differently. For example, you come across an interesting article or video and you want to develop a PPP class around it. So you still might start with objectives to determine what your goals of the class should be, but you might want to play around with developing your Input tasks after that, and then work in the other stages. Whatever works for you.

3) Get everything ready you need to carry out your lesson plan. – links, worksheets, readings or listenings

●What do your students need?

●What do you need?

If they are doing a reading but some changes have to be made (tweak some of the more difficult vocabulary or sections or maybe just use a few excerpts because it is too long for your purposes), prepare it so it is ready to present to them, thinking of how many copies and in what format.

Do they need a worksheet? Again, think of the Presentation and later Practice stages. Maybe the students can complete a chart during the Presentation stage which would be useful when doing the first few Practice activities. Are the worksheet exercises specific to what your objectives are, or do they include other elements that may add to or distract from your proposed class? For example, would it be helpful to review something before entering the Presentation stage?

Do you have an answer key or notes for quick reference if necessary? Maybe for one tricky part of your lesson plan you can write out some specialized notes on a separate paper just for that one section.

4) Go through the logistics of your plan. Imagine the class happening in your mind.

●Is the flow logical and smooth so that the students can get to the Production stage easily?

●Think of allotting time to each activity

●Is the space in the room well-used and should any handouts / use of books etc be done differently?

Maybe you want to change the order of two of the Practice activities. Maybe you realize that the students won’t be sufficiently prepared to do the Production stage and you need to add another Practice activity.

Will you have enough time to do everything? How can you best use the time you have in your class? What can be shortened? What activities might take longer than anticipated (and why)? What if you finish the class sooner than expected? Do you have any backup activities, just in case?

Think of the dynamics of the class. Maybe it would be wise to have students change partners a couple of times and you can do that easily by having one row of students turn around to speak with those behind them. Or when you want the students to turn over their books/papers and what purposes that might serve. Enough photocopies or flashcards for all students? Is there an empty space at the back, front or side of the room that could be used? Can the tables or chairs be moved and how could that add to the class or a particular activity?

5) Final check. Run through it one more time, anticipating problems.

●Timing estimates may be off

●Objectives have changed or are not really worked on

●Other priorities

●Official form to complete

●Your personalized lesson plan

Think of backup – something to do if you finish early or have additional material/activities handy if students need further clarification/practice.

Sometimes the objectives may have shifted focus during the development of the lesson planning. Do you now have a different goal for the class? Will those activities really help the student in terms of reaching your goals? Any modifications necessary?

You may also have some personal goals to work on, for example, such as improving your board work or eliciting techniques. Maybe you can have another look at how you plan to approach the class. For example, you realize that it’s almost all teacher-to-student or student-to-teacher interactions and you want to have more pair-work and small groups, so you make a few adjustments to accommodate that.

You feel good about your lesson plan. Now you can transfer the information (if necessary) to the template that the school is asking you to complete. Make sure you have your own teacher-friendly version of a lesson plan to be at your side when you are actually teaching the class.

Make sure you have a lesson plan which is teacher-friendly for the way you do things. Make it any way that helps you, because it is just for you to use while you are teaching.

B A FEW MORE TIPS

A few useful reminders and suggestions

1– Some tips on finding a good Input

This might help you when you are considering some input text (reading, listening or watching a video)

Go through the text to make sure it’s the right level for the class, and if the contents would be relevant or interesting to your students. You are also looking for a text that reflects the theme for the class and has some of the target language in it.

Is the text too long or too difficult in some places? Do you need to tweak it a bit by cutting out a few sections or changing the wording at times?

Finding the perfect reading or listening or video is sometimes impossible. Rather than spending four hours in your hunt, give yourself 30 minutes as a maximum time limit. If after 20 minutes of looking for a reading without success, consider a listening, and if there’s nothing there, think of what you’d like, work out a quick dialogue and record it with a friend or colleague on your cellphone. Then you can get on with the other parts of the lesson plan (including coming up with the Input questions for the two tasks).

If you have access to different student books, look through books other than the one you are using with your class as resource material, including a level higher or lower. You can use the activity as presented in the book or modify it so it better suits your purposes. For example, with the original reading text (and accompanying exercises) in the student book, you could change it to better suit your needs. Here are some ways you could modify it:

- Add more (more questions, themes to talk about, points to cover if there is a presentation of some language).

●Eliminate parts that you don’t find interesting or useful.

●Re-write some parts to make it more appropriate (maybe grading the language to make it more understandable or so it includes some key elements that you’d like the students to investigate).

●Re-order some of the activities. Perhaps in the course book there is some important vocabulary taught before the reading but you prefer the students have a look at that vocabulary after the reading to see if they can work out the meaning from the context.

●Re-think how you want to deal with the material. Maybe you like the text but want the students to make summaries or to change it themselves in certain ways that reflect different objectives than those set out in the book. Maybe you can make the grammar exercise into some kind of game or a speaking activity.

●Replace one or more parts with something you like more (the actual reading or listening, or maybe one or more exercises or speaking activities).

2— Some examples to consider for target language in your language focus:

Remember that an important criteria to choose the PPP model is in presenting certain language structures, and not to only explore and develop the students’ reading skills, for example. The text can reinforce some skills (like reading for gist or specific information) and that is a part of how the model is used, but it is not the main focus. Here are some examples of different kinds of target language what one could focus on while using the PPP model:

- Vocabulary work

– different kinds of adjectives (ex: -ing and –ed forms or graded vs absolute forms such as hungry vs starving, cold vs freezing)

– different kinds of adverbs (style or manner ex: quickly // frequency ex: once in a blue moon, hardly ever)

– compound nouns or phrasal verbs

– word-formation or transformations where you change one type of word to another

ex: adjective to noun and vice versa hot – heat boredom – boring / bored

– themed sets (examples of vocabulary which are connected by a particular theme)

ex: words related to pollution // objects found in the kitchen or office // different kinds of movie genres // types of clothing // parts of a car

NOTE: Sometimes investigating vocabulary can also lead to some grammar work as well, especially when certain rules of formation or application are explored. If the rules or tendencies are something that can be reasonably identified and useful, then it might be good to dedicate some time to them.

- Grammar

– use of relative clauses, how phrasal verbs are formed and the different characteristics certain types possess, verb tenses, word order, sentence structure, etc

- Functional language

– discourse markers (apparently, surprisingly) // agreement (I agree with you/that up to a point, Really?) - Pronunciation

– sounds, difficult sounds, consonant clusters, word stress, sentence stress, rhythm, intonation patterns, connected speech

3– Some typical obstacles that block or discourage teachers during their lesson planning:

●Not having any direction. If there are any parts that are unclear to you (ex: what ‘input’ is and what you should do in that stage), then refer to the ‘chuleta’ or look up that section again in Part 1 (The PPP Model Explained).

- Don’t know how to structure your lesson plan. When coming up with a plan, follow a format in a way that you can organize it. If you have to hand your plan over to somebody else which requires you to complete it in a certain way, approach your lesson planning with that in mind. If it’s just for you, try sketching out your plan in rough form first and then fill in the details. Look at the examples on this website and on others for ideas. Remember that when you are actually teaching the class, use a format of the plan that you can easily follow.

●Difficult areas such as understanding a grammar point. There are many very difficult areas to learn about and this can be overwhelming for teachers. Grammar is but one such area. Often native English teachers struggle with this more as many non-native teachers are accustomed to learning a lot about the grammar of their language and can apply their knowledge and skills to when they look at and teach the English language. Natives have to relearn their own language it terms of how it’s structured so they can be in a position to teach it.

If you’re not familiar with grammar, accept that it will take many years before you become comfortable with many of its components. Teacher’s books, grammar books, websites, appendices at the back of student books, and colleagues are all good possible sources to clarify some doubts and to gain a better understanding, not only of the grammar, but how one could go about teaching it.

Grammar is just one area that can be difficult to get a handle on. Pronunciation, classroom management, kids vs adults, online vs presential, one-to-one vs small vs big groups, mixed levels/needs, improving the 4 skills, student confidence and motivation, time management, etc, etc, etc. There are lots of areas that you will encounter that are potentially overwhelming at first. When dealing with one area, try to focus in on one or two key points. Try to gain as much understanding as you can through research, exploration and reflection, even reading some ideas over a few times to work out their meaning. Try to identify with specific questions what it is that is stumping you so you can later ask someone. It is easier to ask for and receive help when the questions are more concrete and directed.

Even if you don’t know much about what you have to teach in tomorrow’s class, focus on those things you do (sort of) know, and teach that. As you teach those same points in the future with other groups, it will begin to become more familiar and less intimidating. Little by little you can add to the depth and breadth of those once formidable areas.

- You don’t know what to do in your next class. Keep a little notebook handy that lists themes which interest your students and activities your students like to engage in. (You get this list from a Needs Analysis activity – you ask your students – this can be done on the first day or so of the course, or later if you feel it’s relevant.) Also, in that same notebook, have a section of notes that you can add to as you see what difficulties students have and might need help with during your many classes together. This could be specific grammar or lexical areas, a need for fun activities, a need to build up risk-taking or cooperative behaviour, or other skills to develop (how to communicate with limited vocabulary, fluency, summarizing, description-making, etc.)

4– Adding to your lesson plan while teaching the class

Leave a little space in your lesson plan in the margins and between sections so you can write a quick note or two if something occurs (an observation or an idea, for example) and you want to remember it.

If you will continue being the teacher for this group, plan your next class immediately after this one. Of course this may not be practical because you might have another two classes immediately following the current one, or that you have to leave right after the class. However, you will find that many of your best ideas will come while this class is still fresh in your mind. If it’s a weekly class and you put off the lesson plan until the night before the next time you meet, you might need some time to orientate yourself on what you have done and what you’d like to do. If you can at least scratch out a few ideas shortly after (or during) the class, they will be there to help you when you sit down to work out the next lesson plan. During the class itself many ideas and perspectives surface such as students need to work more on X and Y. If you jot that down somewhere on your lesson plan while teaching the class, then that will help give you direction. Also, get into the habit of checking things off on your lesson plan as you do them This can help you some days later when you’re trying to recall if you actually did what you intended or not.

Save your lesson plans and materials in some way, so you don’t have to start from scratch the next time you have a group to teach at that level. Expect changes in your perspectives, the needs and ways of your students, coursebooks and ways your school wants you to approach teaching. Even with frequent changes, it’s still handy to have something you are familiar with to use as a base, if you like.

5– Some final food for thought

It is hard to get acquainted with a model that is new and even harder to use it in your own lesson planning. It isn’t necessarily simply following a formula and out it comes. It might involve using skills different to those you are accustomed to. For example, many teachers feel more familiar with lecturing and the inclusion of elicitation as one of the active ingredients in the lesson plan could be sufficient by itself to fill the teacher with many doubts.

However, for those who are looking for direction and rationale within their lesson planning, the investment of effort is well worth it. And once you begin mastering it and feeling some confidence in knowing what you’re doing in your lesson planning, you can also begin experimenting with it. Depending on your needs (objectives, situation with the students, etc), you can adapt this model better to meet them, and this means not always following it strictly. (If you are currently in a course which requires you to demonstrate a good understanding of the model, it is recommended not to deviate from the model the way your tutors presented it until after the course.)

There are many ways to modify the PPP model. You may want to change the order or break down the stages in a different manner. For example, you may want to have the students engage in a full discussion early in the class and use that as a basis for your presentation (such as highlighting what they still need to work on to have a better conversation). You may want to present one idea (ex: how to respond to what somebody is saying) and follow it up with one or two practice activities. You are still building up to a production activity in this lesson, but making some changes to the original model.

Another adaptation is that because of time or students’ difficulties in understanding or ability to use a new complex grammatical structure, your objective might be to simply raise awareness of the form of the structure. There would still be a presentation and the students would have to identify the target language in a reading or listening text. Then perhaps a little controlled practice and that is all. It may be best to spread the learning and application curve over two or three classes rather than to strive to production in only one.

The model is there as a guide, a tool to use. Understanding it can provide many benefits, especially if you are a teacher new to the field or are looking for new approaches and need something to base your decisions on. Yet teaching should never be done blindly. There are students who respond to different approaches and there are situations that warrant different decisions. And even how you interpret the model can be done in a variety of ways. Practice activities, for example, are not restricted, nor should they be, to exercises in a workbook or handout or even a drag and match video game. You could use realia, improvised speaking, and changing dynamics in controlled role-plays. Each stage and how they link together has a great potential. You are the director working with a multitude of different factors and want to create paths for your students to make progress and increase their skills and confidence as users of this new and curious language. Planning for your coming classes can strengthen that goal and using at least some elements of one or more models is often a very good approach to take. How it is finally put together and put to use is up to you. And don’t be afraid to experiment a little and later reflect on what happened. Much of your learning can stem from that.

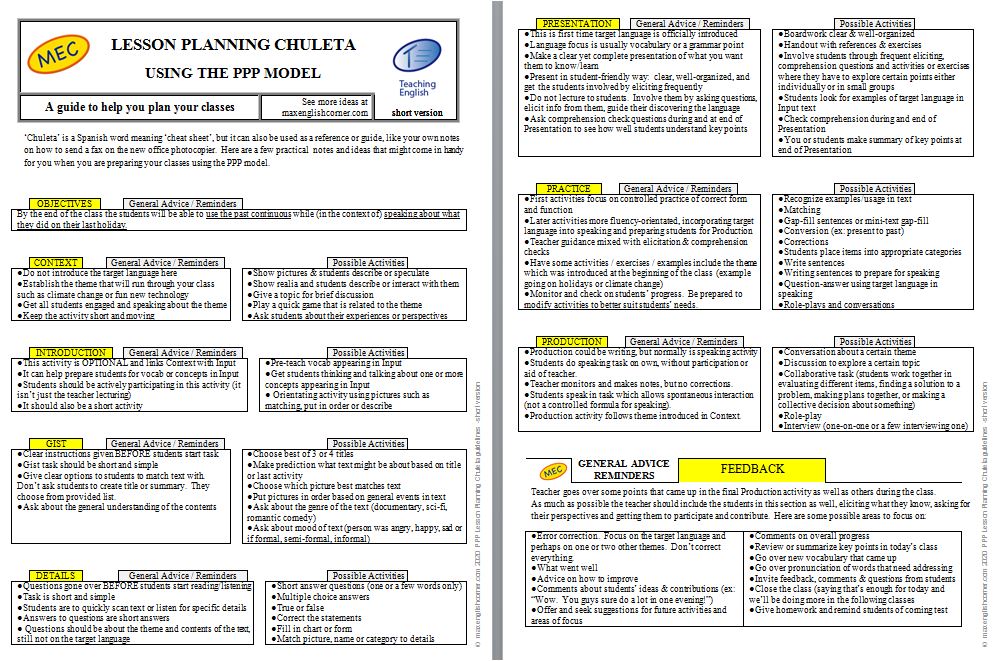

C A CHULETA FOR YOU

Ideas and activities for easy reference

Here is a reference sheet that you might find quite handy when you’re planning your own lessons.

Download or print the version you prefer.

Chuleta – – short version

This short version lists some essential considerations to keep in mind while planning your lesson, as well as a list of several activities you could use for each stage. It is two pages long which is convenient to print onto a single double-sided sheet which you can refer to as you plan your classes.

(Click on Download File for a larger view)

Chuleta – – long version

This longer version is 4 pages in total, covering the same information plus some extra tips that have been suggested in this article. Very useful to refer to, download or print and have at your side when you are planning your classes.

(Click on Download File for a larger view)